A Climate for Pikas

Analysis of habitat helps federal biologists make protection decision

American pikas, little rabbit-like mammals that live on cool and rocky high-altitude slopes, have become a symbol of climate change impacts for some environmental groups. They often cannot tolerate the relative warmth of valleys, and so if climate change forces their preferred habitat upslope, populations could be left isolated, on "sky islands" of good habitat.

In 2007, an environmental group requested that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service assess threats to the mammal- especially climate change- to see if pikas warranted protection under the Endangered Species Act. The FWS sought help from NOAA- the first time NOAA has been involved in a species status review.

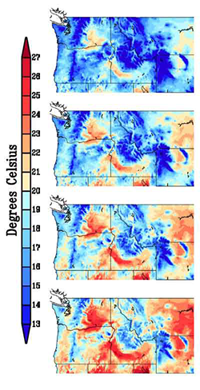

June, July, and August temperatures in the Pacific Northwest, including areas of pika habitat. a) Climatology (1950-1999 average); b) 2025 projection; c) 2050 projection; and d) 2090 projection. Images and downscaled modeling by Jonathan Eishcheid (Physical Sciences Laboratory).

"We were approached by Fish and Wildlife to conduct a rapid review of the area's climate that they could use to inform their decision on pika status," said ESRL's Andrea Ray (Physical Sciences Laboratory, currently on assignment to NOAA's Office of Policy, Planning & Evaluation). "We brought different threads of scientific study together to bear on the particular problem and provided it in about six months so FWS could meet the deadline," she said.

Pikas generally live in alpine and subalpine rockfields, and their range includes mountainous regions from the U.S. and Canadian West.

In February, ESRL's Ray and Joe Barsugli, Klaus Wolter, and Jon Eischeid (all Physical Sciences Laboratory and CIRES) completed a 47-page analysis of observed and projected climate changes in pika habitat. The team assessed climate observations at and near pika locations; and projections from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Fourth Assessment report. They also "downscaled" the IPCC projections to project future climate patterns in 22 specific pika locations.

The research team found that for pika habitat, the average summers of the middle of this century will be warmer than the warmest summers of the past, by about 5°F. Observing stations in parts of Nevada and Oregon, for example, show summertime warming of 2-4°F during the past 30 years. These findings are consistent with the large-scale warming projected by the IPCC global models.

The trends identified in the NOAA report are probably enough to harm some pika populations, especially those in low-elevation, higher-temperature parts of the Great Basin, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service concluded.

"However, these losses will not be on the scale that would cause any species, subspecies or distinct population segments of pika to become endangered in the foreseeable future," the Service wrote, declining to confer protection to the species. "We believe the pika will have enough high elevation habitat to ensure its long-term survival."

By Katy Human, Spring 2010